About DTC and citizen science

IDEA

In this post, I will briefly introduce:

-

direct-to-consumers (DTC) tests

-

citizen and open science projects associated with DTC

HUMAN GENOMES

In 2004, after almost fifteen years of sequencing efforts scientists completed the Human Genome Project (Collins et al. 2003; McPherson et al. 2001; Venter et al. 2001). They identified arrangement of approximately 3 billion bp in the human genome. This project had major influence on the progress of genomics, especially sequencing technologies that were rapidly improved in terms of accuracy, time and money. For example, the cost of the reference human genome was 2.7 billion dollars and this number dropped to 300,000$ in 2006. Today, commercial companies like Veritas Genomics offer to sequence the human genome for 599$ in 26 hours. This trend is expected to stabilize at 100-200$ in the near future. To date more than 1 million human genomes have been sequenced, and this number will likely explode as the cost of genotyping decreases (Stephens et al. 2015).

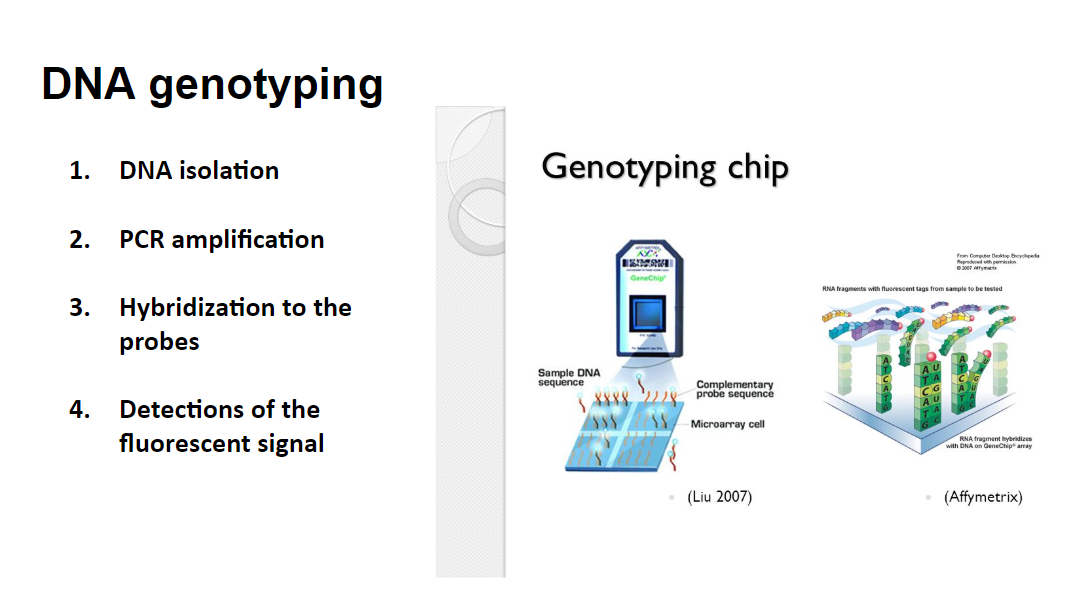

Any two individuals on this planet have 99,9% identical genomes. The 1000 Genomes Project was launched in 2008 with an aim to identify exactly positions in the genome that are different - polymorphisms commonly different between individuals from different populations (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. 2010). Results of that research was implemented in the design of genotyping microarray assays with several hundred thousand locations in the genome that are commonly different between individuals of European ancestry. Genotypes identified through microarray assays have been commonly used in studies that analyzed genetic susceptibility to different traits or diseases (genome-wide association studies - GWAS).

DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER TESTS

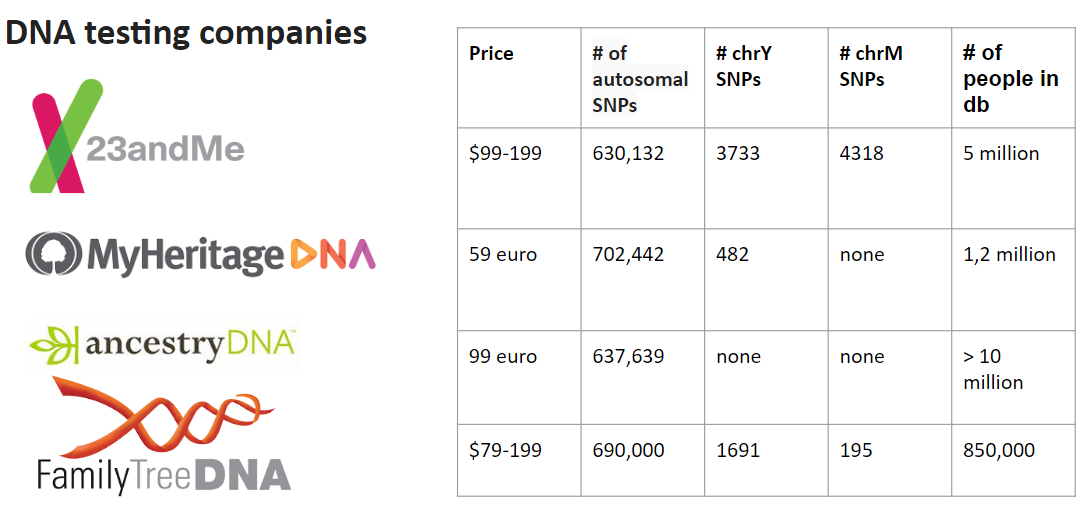

Today, genotyping tests can be purchased directly from the company without the involvement of a health care or scientists (Hogarth et al. 2008). Such tests are referred to as direct-to-consumer tests (DTC) and request the consumer to collect a specimen (saliva) and send it to the company for testing and analysis. DTC tests cost usually between 50 and 200$. The most popular DTC companies are 23andMe, myHeritage, AncestryDNA, etc (isogg.org). Although those DTC tests are banned in some countries such as Germany and France [TO BE ELABORATED IN THE FUTURE], the number of new companies is ever growing due to the public’s desire for direct-to-consumer genetic testing. By 2017, industry estimates report that more than 12 million people had genotyped their genomes.

With easily accessible genotypes, proponents of DTC tests have been emphasizing that they empower consumers to be in charge of their healthcare management (Marietta and McGuire 2009). Along with raw genotypes, companies usually provide additional information - personal ancestry, predictions of predisposition towards different phenotypes such as coffee consumption, athletic performance, lactose intolerance, etc. However, the scope of free-of-additional-charge available bioinformatic analysis differs from company to company. Often, more detailed analysis consumers need to pay to the third party companies.

Many initial tests that assess inherited traits and genetic disorder risks ( 23andMe was offering estimates of “predisposition for more than 90 traits and conditions” in 2008) were suspended by FDA. Thus, US customers who bought tests before November 22, 2013 have online access to their results, while 23andMe’s Canadian and UK locations have access to some, but not all, health-related results. Customers who purchased the test from November 22, 2013 cannot access results, since the tests were suspended until late 2015. Companies also offer customers the opportunity to provide their genotypic and phenotypic information to large research studies.

LIMITATIONS OF DTC TESTS:

skepticism over the scientific validity of tests

Privacy problems and selling data to the third-parties: GSK

Test cover 700K positions, and many risk-associated positions are not tested: example, BRC1 23andMe test SNPs are not covered on the “normal” microarray.

Citizen science projects like PGP, OpenHuman do not exist in Germany

Legislation in Germany - Legislation of direct-to-consumer genetic testing in Europe: a fragmented regulatory landscape

Inequality of genotyping coverage across the World (African Genome Project)

Inequality between companies in quality and quantity of bioinfo analysis

CITIZEN SCIENCE GENOME ANALYSIS

Along with a commercial DTC companies, large-scale studies such as Personal Genome Project (Church 2005) aimed to create a publically available database that stores the complete genomes and medical records. Initially it was launched in the US in 2015 and aimed for 100,000 volunteers. PGP project was extended to Canada in 2012 (Reuter et al. 2018), UK in 2013 (PGP-UK Consortium 2018) , Austria in 2014, Korea 2015 (Zhang et al. 2014) and China 2017. Conceptually, PGP projects are defined as a hybrid between citizen science and scientific research projects. Recently Open Humans platform was initiated. It is a web-interface that allows citizens to upload, connect, and privately store their genetic, activity, or social media data personal data and “donate it”: share publicly, or you contribute to diverse research projects (Greshake Tzovaras et al. 2019).

MY CONTRIBUTION - myDNA R package

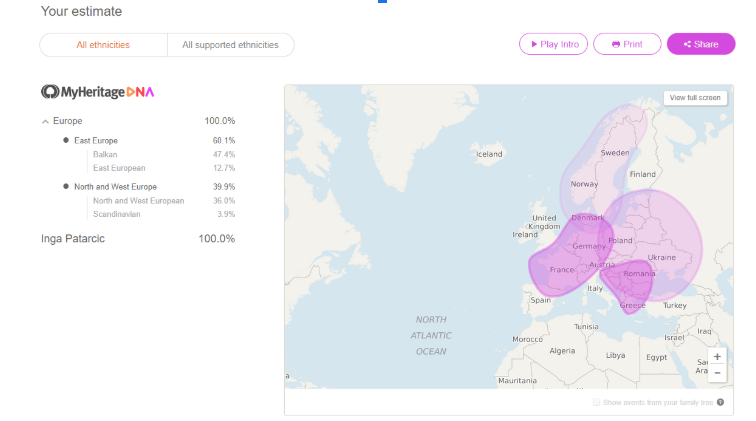

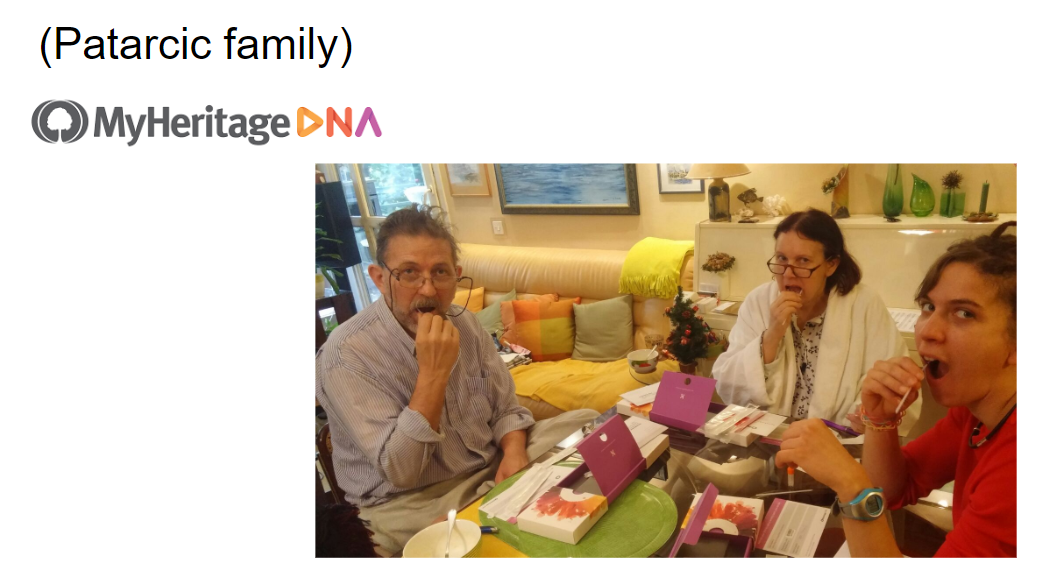

Two years ago, I purchased myHeritage DTC test. Since, I received only my ancestry estimations, I decide to read my own genome as bioinformatician by training. I decided to write reproducible R code and create myDNA package. This package enables you to import your genotypes in R, overlap them with GWAS Catalog and identify risk alleles. It also contains small tests that can directly identify SNPs that are associated with oligogenic traits such as lactose intolerance.

Meanwhile, I wrote an myDNA R package, developed minimal myDNA shinyApp, started myDNA blog. was a project leader at S3++ and educated high-school students genetics, genomics and programming: Analyze myDNA, Internet meets the Human Genome. Analysis of genomes of ancient people reported presented at MDC PhD retreat Presented at Berlin’s Science Week: Soapbox 2009

FUTURE

TBA

LITERATURE

- Church, G. M. The personal genome project. Mol. Syst. Biol. 1, 2005.0030 (2005).

- Reuter, M. S. et al. The Personal Genome Project Canada: findings from whole genome sequences of the inaugural 56 participants. CMAJ 190, E126–E136 (2018).

- Zhang, W. et al. Whole genome sequencing of 35 individuals provides insights into the genetic architecture of Korean population. BMC Bioinformatics 15 Suppl 11, S6 (2014).

- Marietta, C. & McGuire, A. L. Currents in contemporary ethics. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: is it the practice of medicine? J. Law Med. Ethics 37, 369–374 (2009).

- Hogarth, S., Javitt, G. & Melzer, D. The current landscape for direct-to-consumer genetic testing: legal, ethical, and policy issues. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 9, 161–182 (2008).

- Stephens, Z. D. et al. Big data: astronomical or genomical? PLoS Biol. 13, e1002195 (2015).

- Greshake Tzovaras, B. et al. Open Humans: A platform for participant-centered research and personal data exploration. Gigascience 8, (2019).

- PGP-UK Consortium. Personal Genome Project UK (PGP-UK): a research and citizen science hybrid project in support of personalized medicine. BMC Med. Genomics 11, 108 (2018).

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467, 1061–1073 (2010).