A brief history of the human genome

The human genome

The cookbook titled “The human genome”, contains a 3 billion base-pair long set of instructions to build, basically, us. It is written using the four-letter alphabet (A, C, G, T), in a specific order, that allows the precise execution of chemical reactions which underlie human development, maintenance of the cell specificity and reactions to external stimuli. Sequencing of the human genome - as a project finished twenty years ago - identified the order of As, Cs, Gs and Ts. It also unveiled that humans are 99.9% alike. So how come we all are so different? Not only on the outside, but also in the way we react to for example diet or pathogen infections? Is our genetic susceptibility to diseases written in the sequence of those four letters?

Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome

A distributor element of the hereditary information was not known until Gregor Mendel, in 1866, postulated the notion of the gene (Mendel 1866). Throughout the twentieth century, genes were attributed to the chromosomes (Waldeyer 1888, Sutton 1902; Sutton 1903; Boveri 1904) in the genome (Winkler 1920).

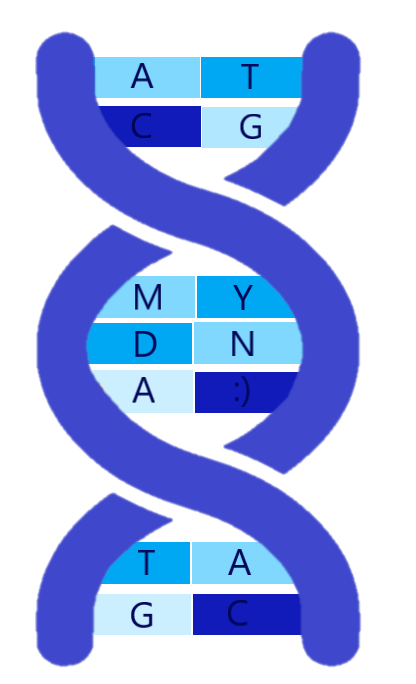

The initial definition of a gene, simply an element of heredity (Mendel 1866), evolved as the knowledge about its physical nature expanded. Physical nature of it (which dictates phenotypic traits of an organism) was attributed to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) - a double helical two-chain molecule composed of covalently bound nucleotides (Figure 1.1, Avery et al. 1944, Hershey and Chase 1952, Franklin and Gosling 1953; Watson and Crick 1953). Each nucleotide was identified to be composed of a nucleobase (four possible nucleobases are: cytosine [C], guanine [G], adenine [A] , thymine [T]) and sugar-phosphate backbone (Kossel 1911) that pair according to Chargaff’s rules within a DNA molecule (Chargaff et al. 1952). Along with DNA, RNA molecules were identified to be a genetic information in some viruses (Wagner et al. 1999).

Recently, in April 2020, I decided to search the web by googling the term “gene” aiming to identify the most recent definition. Among many definitions, I found the following:

“Gene is a specific sequence of nucleotides in DNA or RNA that is located usually on a chromosome and that is the functional unit of inheritance controlling the transmission and expression of one or more traits by specifying the structure of a particular polypeptide and especially a protein or controlling the function of other genetic material.”

.....

The “junk” DNA

Genes are not the only functional elements coded in DNA.

The era of annotating genome(s) - attaching biological information to sequences - started with the development of DNA sequencing methods (Sanger et al. 1977; Maxam and Gilbert 1977). The first sequenced gene was the gene for Bacteriophage MS2 coat protein (Min Jou et al. 1972). Later, the same group of scientists determined the first two genomes - the complete sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA (Fiers et al. 1976) and Simian virus 40 (Fiers et al. 1978).

In the second half of the twentieth century, many teams focused on sequencing the entire genomes. However, the ultimate goal was always to sequence the human genome. Nonetheless, in eukaryotes, genes sequences were found to be interrupted by the elements that do not directly code for proteins: introns or intervening sequences; whereas coding or expressed nucleotide sequences were named exons (Berget et al. 1977; Chow et al. 1977). Soon, the vast majority of the genome (98%) was attributed not to code for genes. Initially, non-coding regions were considered to represent a sequence of DNA without any biological function - the “junk” DNA (Gregory 2011), and only relatively recently, the “junk DNA” regions were found to harbor various functional sequences including regulatory elements such as enhancers, promoters or silencers. In addition, sequences that code for long non-coding RNAs were discovered (Kapranov et al. 2007). Today, approximately 20,000 protein-coding, 10,000 long non-coding RNA genes and millions of regulatory regions have been identified in the (human) genome (Harrow et al. 2012; ENCODE Project Consortium 2004).

Enhancers and promoters

Gene-proximal promoters and distant enhancers are among the most studied regulatory elements in the human genome (Andersson et al. 2015). Their interactions allow tight spatio-temporal regulation of gene expression in a cell type-specific manner. Although enhancers and promoters share similar characteristics, they are, in general, considered to represent separate classes of regulatory elements (Core et al. 2014, Andersson et al. 2015). Promoters overlap with, or are located close to the transcription start sites of genes (TSS) thereby integrating total regulatory input into the rate of transcriptional initiation. The structure of human gene promoters can be quite complex, typically consisting of a core promoter and nearby (proximal) transcriptional regulatory elements (Lenhard et al. 2012). Promoters, work together with other regulatory regions, like enhancers, to regulate all stages of RNAPII transcription from RNAPII recruitment to transcriptional elongation (Smale and Kadonaga 2003).

Enhancers are the first regulatory DNA elements shown to be involved in differential gene transcription (Gerster et al. 1986). They are generally located up to 1Mb from the transcription start sites of genes (Lettice et al. 2003), and increase gene expression regardless of their position, orientation and distance to the promoter (Banerji et al. 1981; Blackwood and Kadonaga 1998). They do not occur at a defined distance from a TSS (Blackwood and Kadonaga 1998); do not necessarily regulate the closest gene ( (Mifsud et al. 2015; Schoenfelder et al. 2015; Javierre et al. 2016), can regulate more than one gene (Gao et al. 2016; Cao et al. 2017), do not have a specific sequence motif or structure for their univocal genome-wide identification (Visel et al. 2009; Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al. 2015) and are very cell-type specific (Joshi 2014).